We are sad to report that all seven of our English Elm Trees (Ulmus Procera) have succumbed to Dutch Elm Disease. Tree experts believe that this was the only remaining Elm grove of its kind in this country, a true cathedral for tree people. Three of the trees were State Champion Trees of Pennsylvania.

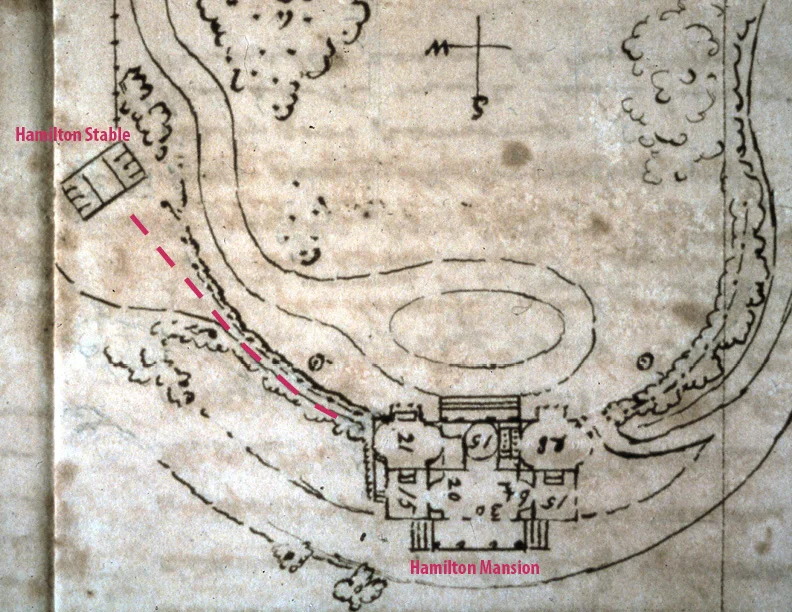

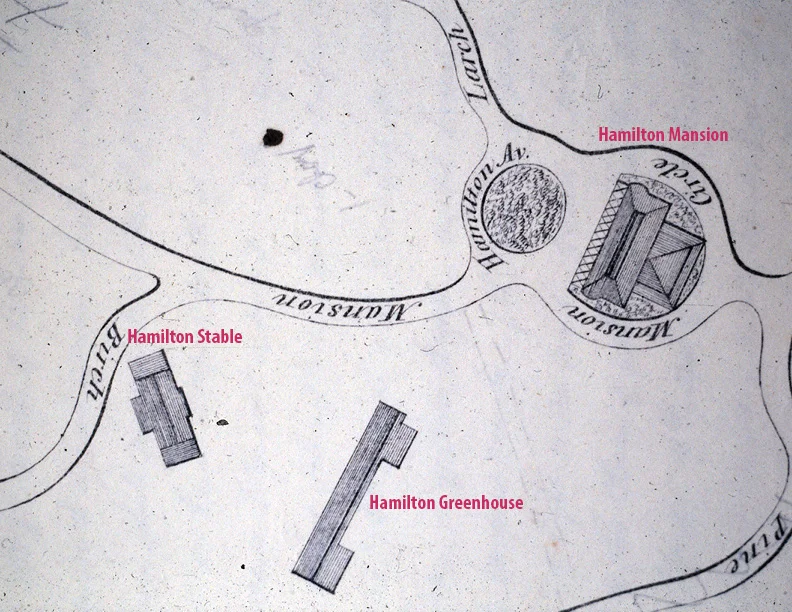

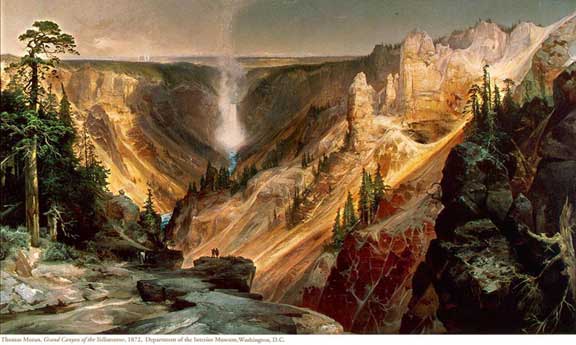

It is possible that there has been an Elm grove to the east of the Hamilton Mansion since William Hamilton lived at The Woodlands in the 18th Century. We know that there was a line of trees in the area where the Elms are that was the border to William Hamilton’s circuit walk. This line of trees can be seen in the below painting of The Woodlands from 1792.

James Peller Malcom (1767-1815), Woodlands, the Seat of W. Hamilton Esq., from the Bridge at Grey's Ferry, ca. 1792. Watercolor and ink on paper, 3-1/2 x 6-1/2 in. Dietrich American Foundation Collection.

When The Woodlands Cemetery Company was founded in 1840, the trees on-site played a major role in the planning of each section, so much so, that the roads throughout the cemetery were named for the types of trees that were most prevalent in that area. Note in the below section map that ELM AVENUE is just to the east of the Hamilton Mansion. This road is adjacent to the grove of Elms.

In 1921, John W. Harshberger, professor of Botany at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote an article for The Garden Magazine on The Woodlands. In this article he describes several trees of significance on the property with measurements, including two large English Elms.

… Near the Ginkgo trees is a Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) with a stem circumference of 1 ft. 5 in. A short distance away are two large English Elms (Ulmus campestris). One of them is 10 ft. 1 in. in circumference, the other is 10 ft. 3 in. around. An English Maple (Acer campestre) with numerous sprouts from its base and roots, and in vigorous health notwithstanding the clouds of smoke from the nearby railroads and manufacturing plants, is 6 ft. 9 in. in circumference. Here also are found descendants of the first Ailanthus tree planted in America by William Hamilton in 1784. There are also several other noteworthy trees, tabulated as follows: Buckeye (Aesculus flava) 5 ft. 3 in. in circumference; Catalpa (Catalpa speciosa) 8 ft. 9 in.; Honey Locust (Gleditsia triacathos) 9 ft.; Mossy-cup Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) 10 ft. 3 in.

John W. Harshberger, “The Old Gardens of Pennsylvania. VI.—The Woodlands, Former Country Seat of William Hamilton,” The Garden Magazine, vol. 33, no. 2 (April 1921), p. 130-133. Read the full article here.

In late May (2014) The Woodlands discovered that several of the Elms in this historic grove were exhibiting signs of Dutch elm disease. Testing confirmed the infection, and treatment on the trees was started immediately. Unfortunately, three of the trees required immediate removal in an effort to protect the remaining Elms from infection. The remaining four trees were inoculated in an attempt to keep them disease free, an effort that was made with the support of The Woodlands community.

Despite these efforts, last summer all four of these remaining elms began to show symptoms of Dutch elm disease, and by the end of the summer, the trees were fully infected. The Woodlands will begin removal of the remaining four trees over the next few weeks, as the limbs are considered a danger to visitors, as well as a threat to the headstones that rest below. We will leave significant portions of the trunks of these trees as a reminder of their massive presence in the landscape, and as a habitat for wildlife. In addition, we are looking for creative uses for the wood from these trees.

Please join us to celebrate the life of these magnificent trees on Thursday, March 9th from 4PM-6PM. Donations in honor of the English Elm Grove can be made to The Woodlands Tree fund, a fund that has been created to propagate significant trees on the property and ensure continuous tree replanting throughout the grounds.