This year’s political processes have been rightly described as messy, but they’re not unprecedentedly so. A century ago, women could not legally vote and two centuries ago, neither could people of color. The struggle to extend voting rights to all Americans was a long one, in which some of the country’s most ignoble fears and prejudices were revealed. Yet, and not without the prolonged work of activists and advocates, progress was made. One influential political mover was Mary Grew, a nineteenth century woman who dedicated her life’s work to fighting for women’s suffrage and the abolition of slavery, and who is buried at The Woodlands Cemetery.

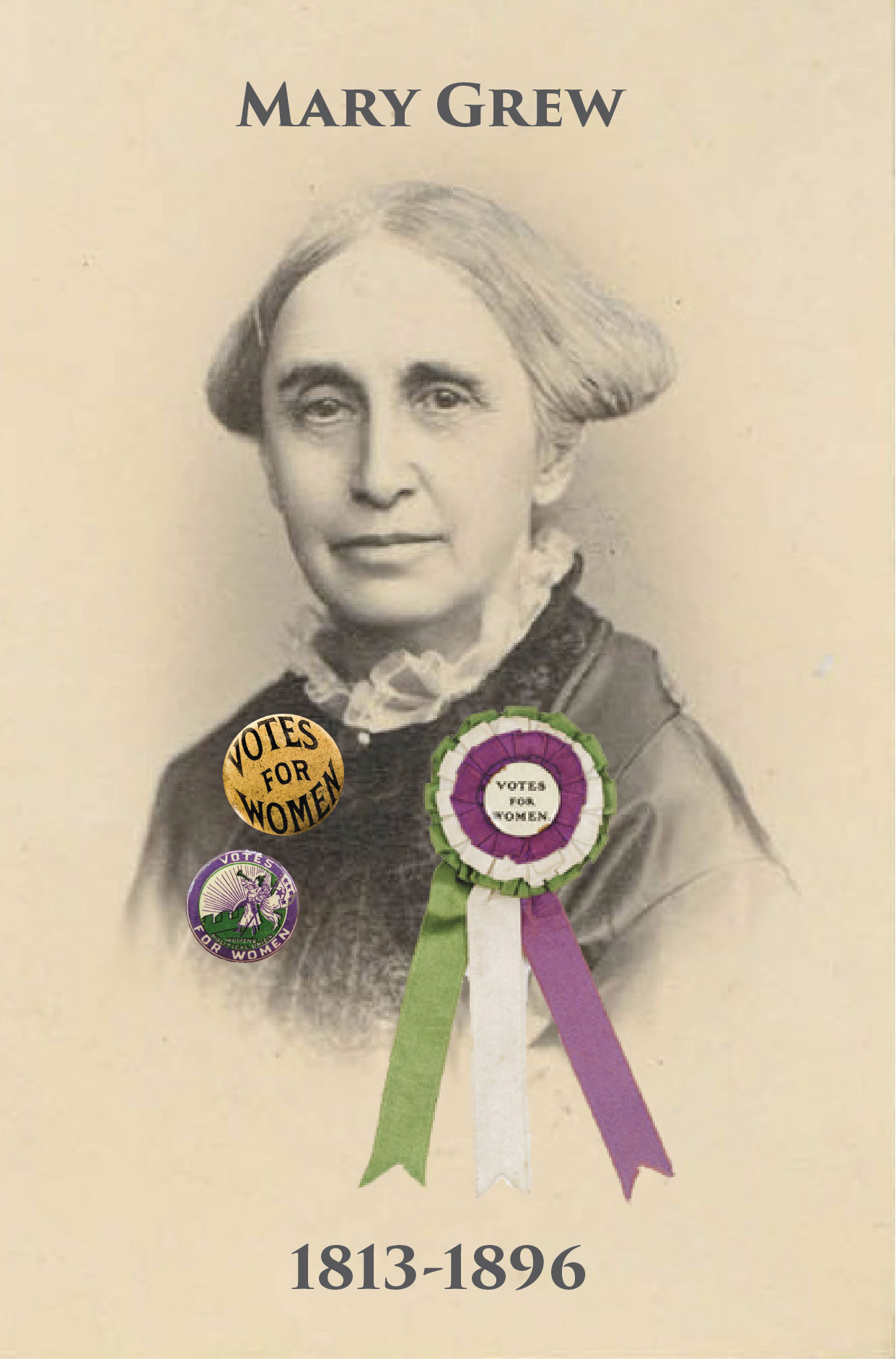

Portrait of Mary Grew

Mary Grew was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1813. Her early life was surely shaped by the then-unconventional spiritual, moral and political positions of her father. Henry Grew was a writer and abolitionist whose rigid and radical interpretations of scripture brought a quick end to his career as a pastor at the First Baptist Church of Hartford. Despite Henry’s resignation (or perhaps deposition) from the clergy, the Grew family was materially comfortable and Mary received a strong education at the Hartford Female Seminary. This school, run by Catharine Beecher, was considered unorthodox for following the standard curriculum of contemporary boys’ schools and giving little attention to the “domestic and ornamental arts.”

In 1834, when she was twenty-one years old, Mary Grew’s entire family moved to Philadelphia, possibly to take a more active hand in the abolitionist movement. At the time, Philadelphia was an important locus of anti-slavery activism, and Mary Grew soon became acquainted with some of the influential female social reformers of her day including Lucretia Mott, Sarah and Angelina Grimke and Abigail May Alcott (the mother of novelist Louisa May Alcott). Mary Grew joined the newly established Female Anti-Slavery Society, where she would serve as the corresponding secretary for nearly three decades.

In this capacity, Mary was instrumental in organizing the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in New York City in 1837. Following the success of this meeting, the Philadelphia delegates to the convention dedicated themselves to raising funds for the construction of Pennsylvania Hall, an abolitionist assembly place. The hall was finished just in time for the second annual Anti-Slavery Convention of American women, but from the first day of the conference, conflict was imminent.

As the women convened, inflammatory pamphlets were scattered across the city, urging “citizens entertaining a proper respect for the right of property and the Constitution of these states” to bring about the “immediate dispersion” of the convention. By the time of a public meeting the next evening, rioters had surrounded Pennsylvania Hall and began throwing rocks at the building. With impressive determination, the “mixed audience of men and women, white and black” continued their meeting, even as the brand-new building’s windows were shattered. On the evening of the conference’s third day, perhaps encouraged by an apathetic show of resistance on the part of Mayor John Swift and the Fire Department, the rioters broke into Pennsylvania Hall and burnt the building to the ground. It must have been with full knowledge of her opponents’ capacity for violence, as well as with some irony, that in the process of planning the third annual convention, Grew told a friend that the “City of Brotherly Love” would “endeavor to give you a better reception, and accommodations, than you met with last spring."

Depiction of Pennsylvania Hall which was burned to the ground by anti-black rioters on the night of May 17, 1838. The structure stood a mere three days before being burned down.

Abolitionism was extremely controversial, yet women activists faced particular ire from both within and outside of the anti-slavery movement. A New York newspaper reporting on the arson of Pennsylvania Hall suggested, “females who so far forget the province of their sex as to perambulate the country” attending political meetings should be “sent to insane asylums.” Many male abolitionists held similar views on the impropriety of women in the public sphere or feared that the controversial presence of women in the movement would hurt an already contentious political cause. The Female Anti-Slavery Society existed in the first place because the American Anti-Slavery Society was not open to women until 1840. And for Mary Grew, sexist objections to her political vocality came not just from inside the abolitionist movement, but from inside her own family as well.

As historian Bruce Dorsey explains in Reforming Men & Women: Gender in the Antebellum City, Henry Grew had made it “his particular calling to remind other abolitionists that the Bible (in his opinion) confirmed a woman’s subordination to men.” This tendency was prominently displayed in 1840, when he, Mary Grew, and a number of other influential American abolitionists travelled to London for the first World Anti-Slavery Convention. Upon their arrival at the convention, the women delegates were informed by the British conference organizers that they were unwelcome; they could observe the proceedings from the gallery of the assembly room, but were not permitted to speak. Some delegates, including the Massachusetts minister and politician George Bradburn (with whom, according to Lucretia Mott, Mary was “quite intimate”) strongly opposed the segregation of the convention. Others, including Henry Grew, supported it. Despite the fact that it would debar his own daughter, Henry claimed that the exclusion of women from the conference was not only fitting with British custom, but also “the ordinance of Almighty God!”

One can only imagine how humiliating and disappointing this rejection would have been for the women who had travelled from the United States to participate in the conference. Fortunately, it also proved galvanizing. For these delegates (and perhaps for the voting-rights movement as a whole) the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention was a turning point, after which abolition and women’s suffrage were not so cleanly divisible. The Convention exposed a contradiction in the abolitionism of the early nineteenth century, which decried racial inequality while remaining silent or complicit in the matter of gender inequality.

After their return to the United States, the female delegates resumed their abolitionist organizing, but also took active steps towards expanding women’s rights. Driven by the shared experience of ostracism at the World Anti-Slavery Convention, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott began planning the Seneca Falls Convention, which eventually took place in 1848. Mary Grew assisted in organizing this groundbreaking summit but did not attend, perhaps due to poor health.

Mary did participate, however, in the fifth Woman’s Rights Convention held in Philadelphia in 1854. As Dorsey explains, “Henry Grew made a habit of following Mary to abolitionist and woman’s rights meetings” where he would vocalize his strong contrary opinions. At the 1854 convention, while his daughter was sitting on the speaker’s platform, Henry Grew took the opportunity to “express his disagreement with the proceedings” and quote bible passages that supported his conviction “that man should be superior in power and authority to woman.” Lucretia Mott executed an effective takedown of Henry Grew’s argument, yet the entire episode could not have been easy for Mary. Still, even with her father’s interference, Mary Grew sustained her involvement in the Woman’s Rights Conventions and a few years later delivered the closing address at the 1860 meeting.

Grew’s increased interest in women’s suffrage and equal rights did not lessen her commitment to abolition. In fact, her dedication to fighting the institution of slavery is reinforced by the fact that she did not assume a major leadership role in the women’s rights movement until 1870, at which point the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments had been ratified and the Female Anti-Slavery Society officially disbanded.

Mary Grew served as the president of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association for over two decades until ill health prompted her to retire in 1892. There is something tragic about the fact that even though Grew spent her entire adult life fighting for the expansion of voting rights to all Americans, she herself was never able to cast a ballot. Mary Grew died in 1896, a full twenty-four years before women received the right to vote in the United States. Still, she worked to bring about some of the most remarkable social and political progress the country has seen, and the story of her long career deepens the meaning of enfranchisement in 2016. Today, as in Mary Grew’s time, egalitarianism is not a political certainty, a fact which makes the exercise of the of the voting rights she fought for all the more important.

Want to visit Mary's gravesite? She is located in Section C, Lot 559. Download a section map of the cemetery here.

-By Rive Cadwallader