PHILADELPHIA, April. 15 — This is a PSA and a call for support from The Woodlands community to help spread the word: people have been taking flowers from The Woodlands and this is unacceptable. Twice this week alone, visitors were seen removing flowers from the cemetery for their personal use, including cuttings from Grave Gardens and our flowering trees.

Read MoreRoots Of The Ginkgo

Recognized by their unique, fan-shaped leaves, the Ginkgo biloba is a common tree in Philadelphia. You've probably seen them lining Spruce Street in Center City, but did you know the first Ginkgo trees were introduced to the United States by The Woodlands’ own William Hamilton?

In 1785, Hamilton sent three trees to The Woodlands, planting two in his own garden and gifting the third to his friend down river, William Bartram. The original trees planted at The Woodlands are no longer alive, but the tradition continues with over 20 ginkgos in varying sizes spread throughout the grounds. You can still find the original gifted ginkgo at Batram’s Garden today - it’s one of the oldest in the country.

The vibrant saffron color of the foliage only lasted briefly this year. When we visited the trees on the morning of November 13th, all the leaves had fallen overnight. Ginkgo trees loose all their leaves at once when a cold frost hits, unlike other trees who lose their leaves over the course of a few days or weeks. With over 1,000 trees onsite, you can visit The Woodlands in the next few weeks to see the other trees hitting their peak fall foliage.

Photo taken on Tuesday, November 12th.

Written by:

Julia Griffith and Emma Max

Photo taken on Wednesday, November 13th.

Hamilton’s Trees Live On

In 1876 Eli K. Price, one of the founders of The Woodlands Cemetery Company, wrote in The Gardener’s Monthly:

“These trees will be cared for and preserved in the Woodlands. What is more important is, that they should be secured to our country by propagation. If seed should appear next Fall, they will be gathered. In the meantime grafting should be attempted. Mr. Sargent is trying it at Cambridge, on English elms. I invite gardeners to get cuttings and try their success.”

Carrying this ethos into the twenty first century, Executive Director Jessica Baumert reached out to Philadelphia’s tree experts in 2014 for help propagating some of the significant trees of The Woodlands as Dutch Elm Disease took hold in the Grove of Seven Giants. Tony Aiello of Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania graciously offered their propagation facilities and this fall The Woodlands staff took a field trip to visit the resulting Caucasian Zelkova (Zelkova carpinifolia) and English Elm (Ulmus procera) saplings. In the expert hands of Morris propagators Shelley Dillard and Steve Pyne, cuttings taken in the summer of 2014 are now growing ready to be planted back at The Woodlands.

While unassuming in appearance now, these toddler trees have formidable ancestors. English Elms and Caucasian Zelkovas have been part of The Woodlands landscape since William Hamilton’s time. More recently the English Elm grove of Seven Giants was one of the oldest remaining of its kind before succumbing to Dutch Elm disease in 2014 and 2016. It will be a challenge to reestablish an elm grove at The Woodlands because the disease is on the property, but for now the genetic material of the Grove of Seven Giants lives on.

Remaining four trunks of the Grove of Seven Giants. Photo taken by Ryan Collerd at the English Elm Memorial Service in March, 2017.

The Caucasian Zelkova near the Hamilton Mansion is perhaps The Woodlands most photogenic tree resident. Native to the Caucasus region of Eurasia, this species of zelkova was introduced to North America by William Hamilton. Visitors to Hamilton described a double row along the driveway between the Stable and Mansion. Can you imagine walking through a tunnel of eight of our fairytale trees? By 1916 only one Hamilton’s planting was still living and by 1921 it was also dead. The Caucasian Zelkova lived on, however, in the form of root suckers of one of those original trees which grew into the specimen we see today.

Just as contemplating the lives of Hamilton’s era or the many people buried here can connect us to the community and history of this site, so can consideration of its trees. Our trees bear witness from the past with scars from injury or trunks leaning out of the shade of a neighbor tree no longer there. They also enrich the present by providing wildlife habitat, cooling shade, and cleaner air (not to mention beauty). And best of all, each year’s new growth reminds us of their resilience and durable presence.

Planting the next generation of English Elms and Caucasian Zelkovas in 2019 will coincide with The Woodlands’ pursuit of arboretum accreditation. The accreditation process involves updating our tree database with recent additions and losses as well as formalizing our policies for caring for and building our collection of over 1,000 trees. We look forward to sharing our progress as we continue caring for the horticultural legacy of The Woodlands, and in the meantime, please enjoy these photos from our recent trip to the Morris Arboretum.

Written by Robin Rick, Facilities and Landscape Manager

William Bartram's Travels and the Early Naturalist's Library

By Joel Fry

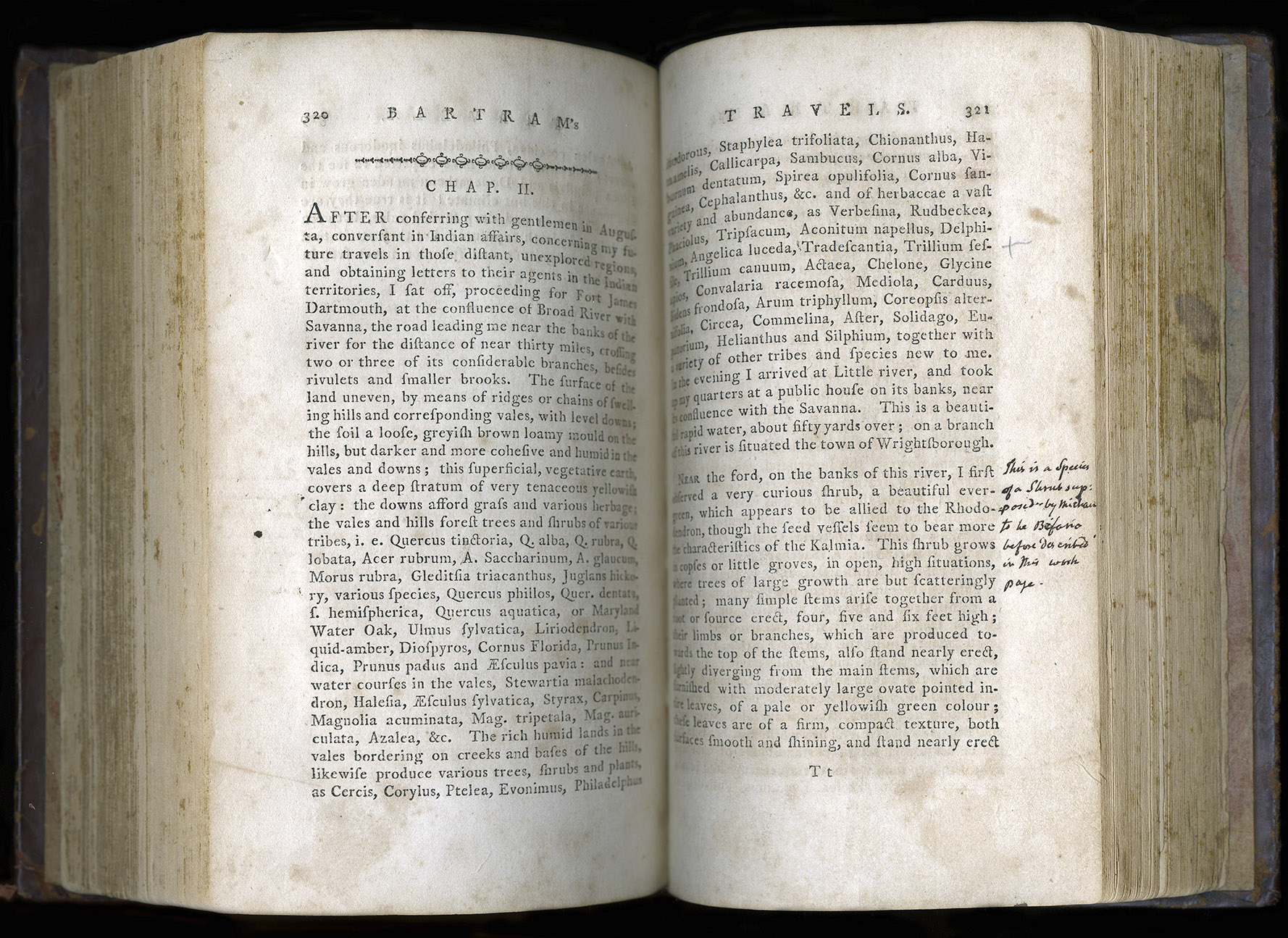

William Bartram's reputation as a botanist, naturalist, and explorer has endured in the modern world largely due to his single, classic book: Travels through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws… Printed by James & Johnson, Philadelphia, 1791. William Hamilton had an extensive library and owned at least two copies of the book authored by his friend. One of his copies is now housed at the Sterling Morton Library at the Morton Arboretum in Lisle, IL and offers an interesting glimpse into the naturalist's library.

A Map of the Coast of East Florida drawn by William Bartram for Travels. (Image: John Bowman Bartram Special Collections Library)

In vivid text, Travels recounts Bartram’s southern explorations from 1773 to 1776, and documents his encounters with the natural world and with the native and colonial inhabitants of the English colonies along the Southern Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Bartram’s descriptions of Florida and the South captured readers internationally during his life and the book continues to be read widely in modern times. Bartram’s Travels was an unprecedented mix of literary genres—part travel book, part scientific record and description — a romantic narrative, an ethnography of Southern native peoples, and an exposition by Bartram on natural and theological philosophy.

The publication of Travels in Philadelphia in the 1790s was an expensive undertaking. A large book, running over 522 text pages with an additional introduction, the original edition included illustrations and a map by William Bartram. It took two subscription efforts to get the book to print, in what was a risky publishing effort in post-revolution Philadelphia. The first subscription effort for the book in 1786, by the Quaker printer Enoch Story, Jr. failed, perhaps for financial reasons, but also in part because William Bartram suffered a life-threatening fall and compound fracture at the ankle while gathering bald cypress seeds at Bartram’s Garden in fall 1786. It took over a year for Bartram to recover. A second broader national subscription for Travels in 1790 by the new firm of Joseph James & Benjamin Johnson in Philadelphia succeeding in seeing the book to print in summer 1791.

It has recently been discovered that Bartram’s Travels was issued in Philadelphia in more than one version. The standard version distributed to most subscribers had frontispiece, map and 7 illustrations. In early 1792 retail copies were also offered for sale with the option of “extra Plates, (eight in number)… either plain or coloured.” These extra plates were larger in size and were folded in thirds to be bound in the book. Currently only 5 sets of these extra illustrations are known.

James Trenchard engravings of two William Bartram drawings from the set of 8 rare extra plates: “Bignonia Bracteata" (left) modernly known as Pinckneya or fevertree and “Franklinia alatamaha” (Image: American Philosophical Socitey Library)

It is not surprising that William Hamilton of The Woodlands seems to have owned at least two copies of the original Philadelphia edition of Bartram’s Travels. “The Woodlands Household Accounts” record payment September 8, 1792: “Bartrams Travels 11 [shillings] 3 [pence]”

Travels as advertised in Dobson and Claypoole's Daily Advertiser, January 4, 1792. (Image courtesy of Jim Green of the Library Company of Philadelphia

This is the equivalent of the $2.00 price for a bound copy of William Bartram’s Travels, but it isn’t known if Hamilton was a subscriber or if he purchased a retail copy in 1792. [Accounts were frequently paid long after the fact in the 18th century.]

So far no trace of this first Hamilton owned copy of Bartram’s Travels has surfaced. A second, fine copy of Travels, with the standard plates colored, and bound with the 8 extra plates colored was presented by William Bartram to William Hamilton in 1799. This presentation copy from 1799 is now owned by the Sterling Morton Library at the Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL.

The Hamilton extra-illustrated copy of Travels, contains a rare copy of William Hamilton’s bookplate under the front cover, engraved with the Hamilton family arms and “W. Hamilton.” William Hamilton was certainly a collector of books, as well as plants, art, statuary and more. Recent research by Villanova students turned up a dozen volumes in Philadelphia area special collections libraries with the Hamilton bookplate or signature. But Hamilton likely owned dozens or even hundreds of volumes on botany, gardening and natural history. One book signed and with the W. Hamilton bookplate is now part of a collection of Bartram family books donated to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in the 1890s by a Bartram descendant. That book. Thomas Martyn, The language of botany…, London: 1796 is a standard dictionary of botanic terms in English. It was probably loaned to William Bartram or another Bartram family member and never returned to Hamilton.

William Hamilton's bookplate, engraved with the Hamilton family arms and “W. Hamilton," graces the inside cover of the copy of Travels held at Morton Arboretum. (Image courtesy of the Sterling Morton Library)

The title page is signed by Hamilton on the upper right; “W. Hamilton’s Book give to him by the Author, June 9th, 1799.” No other documentation about this gift from William Bartram to William Hamilton survives. It may be Hamilton had lost or loaned his original copy of Travels, or he may have wanted an additional copy with the rare extra engraved plates?

It is clear that William Hamilton closely read this copy of Travels, as there are small annotations on several pages – including the addition of the scientific names “Gordonia Franklini” and “Pinckneya” on page 16, where the description of Franklinia was printed facing the two folded extra-illustrations of “Franklinia alatamaha” and “Bignonia bracteata” [modern Pinckneya bracteata, or fevertree].

"W. Hamilton's Book given to him by the Author June 9th, 1799" is inscribed on the cover page. (Image courtesy of the Sterling Morton Library)

Other notes by Hamilton in his extra-illustrated copy of Travels also comment or annotate some of the rarest plants that William Bartram encountered in his trip. And of course there is evidence that Hamilton was growing some of William Bartram’s southern plant discoveries in the garden at The Woodlands. One of the seed packets recently recovered from the attic of The Woodlands was labeled “Hydrangea quercifolia, Bartram’s Travels” and oakleaf hydrangea was another new plant described and illustrated by Bartram in the book.

Hamilton’s note of the scientific name “Gordonia Franklini” for Franklinia references part of a rare illustrated collection of new plants from Paris, published by the botanist Charles Louis L’Héritier de Brutelle in 1791. And the genus name Pinckney was not published as a scientific name until 1803 by the French botanist André Michaux. Hamilton may have learned of both these then current scientific names from Michaux’s Flora. Note the Franklinia plate folded to the right (as shown in the image above). (Image courtesy of the Sterling Morton Library)

A note by Hamilton reads, "“This is a Species of a Shrub supposed by Michaux to be Befaria before described in this work page —.” Interestingly, this plant has gone through three spellings, “Befaria”, “Besaria”, and “Bejaria”. It is now officially called Bejaria racemosa, flyweed, a flowering shrub from Florida discovered by William Bartram. Flyweed as “Befaria hirsuta” was listed for sale as a greenhouse plant in Bartram Catalogues from 1807 onward. (Image courtesy of the Sterling Morton Library)

Hamilton's inscriptions are telling; he only made notations in the botanic sections of Travels, indicating little interest in sections dealing with birds and wildlife, or in the parts dealing with Native peoples — the Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee.

Handwritten “Errata” by William Bartram, slipped in at the end of Hamilton's copy of the book. (Image courtesy of the Sterling Morton Library)

A group of scholars, including Nancy Hoffmann, Bill Cahill, Alina Josan and Joel Fry, are currently working to research and locate copies of the 1791 edition of William Bartram’s Travels, collating a census of copies, and looking for owner’s names, annotations, binding, and general history. The researchers have located over 125 copies, mainly in special collections libraries in the US, and have visited 56 or more copies. Many or most of the copies seem to be subscription copies, and a third or more have a similar original binding. Many of the owners who signed copies were substantial citizens in the early U.S, and local lending libraries around Philadelphia also held a number of copies. Only four are now known bound with the extra plates seen in William Hamilton’s copy at the Morton Arboretum. As of yet, the researchers don’t have a firm knowledge of how many copies of the 1791 Philadelphia edition were printed, but they estimate that it might be on the order of 400 or 500 total.

The lasting fame of Travels is probably due to the widespread European reprints of the book, which began to appear in 1792, a year after the Philadelphia printing. There were English editions of Travels in London in 1792 and 1794, Dublin: 1793; translations into German with editions in Berlin and Vienna: 1793; a Dutch translated edition in Haarlem, 1794-1797; and French translated editions from Paris: 1799 and 1801. These European editions were all based on the 1791 subscription version and copied the standard illustrations, but never included the 8 extra plates.

Stay tuned as we highlight more of the fascinating botanical connections between these two sites!

Previous Posts:

Introducing the Two Williams

Found in the Floorboards: 200 Year Old Seed Packets

Upcoming Posts:

Think Local Swap Global: 18th Century Approaches to Plant Collecting

From Seed Shack to Plant Palace: Evolutions in Greenhouse Technologies

The 19th Century Commercial Nursery

Introducing the Two Williams

Did you know that William Hamilton of The Woodlands and William Bartram of Bartram's Garden were contemporaries and friends? The two shared a love of plant collecting and botany, were neighbors, and were involved in many of the same local institutions! To highlight some of these lesser-known connections, we're bringing you Two Williams: a six month blog series hosted between The Woodlands and Bartram's Garden. Each month, we will dig into the archives and share what we find!

Picturing the banks of the tidal Schuylkill as a lush, pastoral landscape takes a bit of imagination these days. But long before it was home to manufacturing plants and oil refineries, the stretch of the River running through Philadelphia to the Delaware was considered one of the most beautiful scenic landscapes in the country. Though much of this revered landscape was lost as the waterfront industrialized, some vestiges were spared. The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden were both prominent 18th century estates and hubs for the early study of botany and horticulture, separated by just over a mile along the Lower Schuylkill. Safeguarded by early preservation efforts, both are now recognized as National Historic Landmarks, bastions of Philadelphia’s horticultural legacy that live on as parks, historic sites, and important community anchors in their respective neighborhoods.

The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden shown on an 1808 map surveyed and published by John Hills. (Image: Philageohistory.org)

The Woodlands and Bartram’s share a number of historical themes and connections, which we will be exploring in monthly blog posts. This month, we’ll begin by introducing two key players: William Bartram (1739-1823), son of John Bartram and William Hamilton of The Woodlands (1745-1813). The two men were friends and contemporaries (and, notably, both were both lifelong bachelors) passionate about botany and horticulture in distinct yet complimentary ways.

William Hamilton’s mansion as seen from across the river depicted by James Peller Malcom ca. 1792. (Image: Dietrich American Foundation)

Portrait of William Bartram by Charles Wilson Peale, 1808 (Image: Independence National Historical Park)

William Bartram, son of John Bartram (1699-1777), was a gifted naturalist and a very skilled botanical and ornithological artist. Growing up, he accompanied his father on many of his travels and gradually took over the maintenance of the family garden. Later, William spent the years 1773-1776 traveling the southern Colonies studying and collecting plants and animals. He interacted with local Native American tribes and made copious notes and drawings, writing extensively about his findings which were published as Bartram’s Travels in Philadelphia in 1791. Upon returning from his excursion in 1777, William resumed his work maintaining and caring for the family garden and business at Bartram’s with his younger brother John, Jr.

Portrait of William Hamilton and his niece Ann Hamilton Lyle. (Image: Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Just up the river, William Hamilton (grandson of prominent Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton, whose defense of John Peter Zenger established freedom of the press) established his estate, The Woodlands, in the style of an English country house. Hamilton inherited the estate from his father in 1747 when he was just two years old and had, over the course of his adult life, parceled together roughly 500 acres along the western bank, including much of what is now the campuses of Penn and Drexel. Hamilton was an Anglophile and an enthusiastic amateur botanist and plant collector. An extended visit to England in the mid-1780s inspired the neoclassical remodel of his Philadelphia estate, recognized as the earliest example of Federal architecture in the country, and heavily influenced his approach to landscape design. Thomas Jefferson, who was a frequent visitor to both Bartram’s Garden and The Woodlands, once remarked that Hamilton’s estate was “the only rival which I have known in America to what may be seen in England.” Hamilton was particularly interested in collecting rare and exotic plants, introducing a number of exotic species to the U.S. through his massive greenhouse complex which is believed to have housed upwards of 9,000 species.

The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden formed the nexus of the country’s early botany scene and helped spur a regional horticultural economy that persisted for generations. Prominent naturalists, politicians, and members of the gentry would often stop at one or both gardens when travelling into the city. The two Williams frequently connected over their shared interest in plants and botany, often exchanging letters, plants, seeds and services. This relationship is best illustrated in their correspondence, which was frequent and familiar and often involved arranging the viewing, sharing, and trading of plant material.

A photograph of the Gingko at Bartram’s Garden from 1924 captioned “Oldest Gingko in America.” After William Hamilton imported the first Gingko biloba into the country, he kept two on his property at The Woodlands and sent the third as a gift to William Bartram. The two at The Woodlands no longer stand, but the impressive Gingko at Bartram’s still does and is recognized as the oldest living example in North America. (Photo: John Bowman Bartram Special Collections Library)

In a letter[1] to William Bartram on November 7, 1796 Hamilton wrote:

Dear Sir

I must beg the favor of you to make a sketch of the Senecio nova, floribunda as it now blooms in my Hot House. For this obligation I will make you any compensation in my power. After this day it cannot be done this Season as its beauty is already on the decline.

I have moreover in my Hands at this moment, just arrived from England near 100 coloured plates mostly of new plants (some of them from Botany Bay) which you ought not to lose the opportunity of viewing & they are immediately to be return’d to the gentleman who left them here. I hope therefore you will oblige yourself as well as me by coming here as soon as you can after receiving this & that you will come prepared to make the sketch I have required, in which I am more interested for the Honor of American gardening than you are aware of. I have seen a figure & description of this plant as it flower’d last season for the first time in Europe, under the name of Senecio Chrysanthemum by which I find it flower’d with me before it was known in Europe.

I am dear Sir truly

Your friend & humble Servt.

W Hamilton

Both Williams also had connections to the University of Pennsylvania, then known as the College of Philadelphia, particularly to Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, chair of Materia Medica and the sole professor of botany at the university. Bartram’s Garden and The Woodlands functioned as outdoor laboratories to supplement lectures and William Bartram often leant his services as a botanical illustrator to assist Barton. The relationship between the three ensured the university’s position as the best place in the country for the study of botany and both Hamilton and Bartram assisted in procuring and sharing noteworthy and interesting plant specimens. In the following letter, William Bartram writes Dr. Barton about the first blue hydrangea imported to America, on display at William Hamilton’s garden at the Woodlands:

P.S. Come see us as soon as convenient. Have you seen the most beautiful Hydrangia [sic] from china now in flower at Hamiltion’s Gardens at the Woodlands? if not it is well worth a visit. The Cœlestial blue of the flowers is inexpressebly [sic] pleasing. [2]

An Illustration from Frank H. Taylor ca. 1922 showing the Woodlands mansion and John Bartram’s house as examples of country mansions from “a time when the unpolluted tide-water Schuylkill River was bordered by fine country seats.” (Image: Library Company of Philadelphia)

Hamilton frequently entertained guests at The Woodlands and his dinners and his gatherings, more often than not, involved lengthy discussions about plants and botany supplemented by demonstrations of species from his greenhouse. These were sometimes even coordinated around significant bloom times of his most impressive rare species, which would be brought in to the house to be observed and appreciated throughout the meal. In the following letter,[3] Hamilton requests a sample of a particular variety of grape from Bartram to serve the dual purpose of botany and dessert at an upcoming dinner:

My dear Sir

Mr Pursh tells me that he was at your house yesterday & that you shewed him a white grape which you called Blands grape—From what I have heard you say, I have always supposed it a dark fruit & my curiosity is exited to understand the Business. I will therefore thank you to send me a specimen of the fruit by the bearer. If it is ripe & you can spare them, you will oblige me by sending as many as will fill a plate as if the fruit good, it would serve as an interesting part of our Desert [sic] at dinner to day for Mr. & Mrs. Merry whom I expect will be here—

—I am most sincerely

Your friend

W. H.

Stay tuned as we highlight more of the fascinating botanical connections between these two sites!

Upcoming Posts:

Found in the Floorboards: 200 Year Old Seed Packets

William Bartram's Travels and the Early Naturalist's Library

Think Local Swap Global: 18th Century Approaches to Plant Collecting

From Seed Shack to Plant Palace: Evolutions in Greenhouse Technologies

The 19th Century Commercial Nursery

By Starr Herr-Cardillo

[1] William Hamilton to William Bartram, November 7, 1796, Gray Herbarium Autographs 3:17a, Harvard University.

[2] William Bartram to Benjamin Smith Barton, July 16, 1800, Barton Delafield Collection, American Philosophical Society.

[3] William Hamilton to William Bartram, circa 1803-1805, Bartram Papers 4:49b, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

This blog series is made possible by Penn Sustainability and PennDesign.