We can’t get enough of Doris and Denis’ love story! Our neighbors told us the tale of their early courtship at The Woodlands: sitting at the base of Thomas Evans’ tomb, the tallest obelisk in the cemetery, Doris and Denis talked until 3:00 in the morning, the catalyst for their decades-long love.

Read MoreCelebrating Dr. Neville Strumpf

On May 20th, 2019, someone very special to The Woodlands is receiving an Honorary Degree from the University of Pennsylvania!

Dr. Neville Strumpf, one of our board members, will be attending the University of Pennsylvania’s 263rd Commencement ceremony in order to receive her Honorary Degree, which is awarded to only those that represent the highest ideals of the Ivy League school, so I guess you could say this is a pretty big deal. Other people being honored on this day are animal scientist Temple Grandin and singer-songwriter Jon Bon Jovi.

Neville has contributed immensely to the nursing community. After receiving her Bachelor’s from the State University of New York and her master’s at Russell Sage University, Neville decided that she wanted to continue her education even more by receiving her PhD at New York University in 1982.

After her academic success, Neville dedicated her time to researching geriatric nursing, or nursing for elderly patients, trying to implement more ethical treatments into her field. Dozens of her publications ultimately led to more effective, ethical methods to care for geriatric patients.

Neville didn’t stop at the research, though! In the 1980s, Neville helped found several geriatric nursing programs at the University of Pennsylvania to improve the care of older adults. She made an appearance on C-SPAN (1:22:00) representing the National League of Nursing at a Senate Finance Subcommittee on Health meeting to discuss the nursing shortage in 1987. She used her experience to highlight the lack of nurses who were trained to care for the elderly at this time. Her work was crucial to the expansion of Geriatric Nursing in this country.

From 2000-2001, Neville became Interim Dean of the Penn Nursing program. During her time as the Dean, she put her staff and students first to ensure they had the right resources and funding to support research projects and help programs reach their goals. Neville’s service to the nursing field has expanded the way people think about geriatric nursing to aid patients with the best care possible. Read about her work in her book, Restraint-Free Care online.

Neville’s late life partner, Karen Buhler-Wilkerson, worked alongside her in improving the education and research at Penn Nursing. Karen worked as a professor of community health at Penn and also served on the board of The Woodlands. Karen passed away in 2010 and we are honoring her memory as we celebrate Neville’s accomplishments that she supported throughout her life. The Nursing Center remembers Karen’s notable accomplishments, and how she "...helped found Penn Nursing's Living Independently For Elders (LIFE) program, which provides ongoing daily care for 500 poor and frail residents of West Philadelphia." She is buried at The Woodlands and her legacy can be felt at The Woodlands and in the greater Philadelphia community.

Through her work, Neville has exhibited a true dedication to geriatric nursing and patients globally, and has shown that same dedication in other parts of her life. As if all the work she has done wasn’t enough, she is the president of the board at the Ralston Center, a non-profit that focuses on assisting people 55 and older with services to equip them for independent living in their homes and communities. Her work at the Ralston Center revolves around spreading her knowledge of gerontology to others as a respectful leader. Neville truly believes in running a non-profit like a family, utilizing her past experiences to help others become leadership ready. She is also on the advisory board of Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, and, of course, one of our very own board members here at the Woodlands.

Neville has shown an outstanding amount of work and service not only in her field, but in her community. Her honorary degree is extremely well-deserved and we thank Neville for all she has done for The Woodlands. Shout out and HUGE congrats to you, Neville! You rock!

Written by: Alyssa Geniza

Introducing the Two Williams

Did you know that William Hamilton of The Woodlands and William Bartram of Bartram's Garden were contemporaries and friends? The two shared a love of plant collecting and botany, were neighbors, and were involved in many of the same local institutions! To highlight some of these lesser-known connections, we're bringing you Two Williams: a six month blog series hosted between The Woodlands and Bartram's Garden. Each month, we will dig into the archives and share what we find!

Picturing the banks of the tidal Schuylkill as a lush, pastoral landscape takes a bit of imagination these days. But long before it was home to manufacturing plants and oil refineries, the stretch of the River running through Philadelphia to the Delaware was considered one of the most beautiful scenic landscapes in the country. Though much of this revered landscape was lost as the waterfront industrialized, some vestiges were spared. The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden were both prominent 18th century estates and hubs for the early study of botany and horticulture, separated by just over a mile along the Lower Schuylkill. Safeguarded by early preservation efforts, both are now recognized as National Historic Landmarks, bastions of Philadelphia’s horticultural legacy that live on as parks, historic sites, and important community anchors in their respective neighborhoods.

The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden shown on an 1808 map surveyed and published by John Hills. (Image: Philageohistory.org)

The Woodlands and Bartram’s share a number of historical themes and connections, which we will be exploring in monthly blog posts. This month, we’ll begin by introducing two key players: William Bartram (1739-1823), son of John Bartram and William Hamilton of The Woodlands (1745-1813). The two men were friends and contemporaries (and, notably, both were both lifelong bachelors) passionate about botany and horticulture in distinct yet complimentary ways.

William Hamilton’s mansion as seen from across the river depicted by James Peller Malcom ca. 1792. (Image: Dietrich American Foundation)

Portrait of William Bartram by Charles Wilson Peale, 1808 (Image: Independence National Historical Park)

William Bartram, son of John Bartram (1699-1777), was a gifted naturalist and a very skilled botanical and ornithological artist. Growing up, he accompanied his father on many of his travels and gradually took over the maintenance of the family garden. Later, William spent the years 1773-1776 traveling the southern Colonies studying and collecting plants and animals. He interacted with local Native American tribes and made copious notes and drawings, writing extensively about his findings which were published as Bartram’s Travels in Philadelphia in 1791. Upon returning from his excursion in 1777, William resumed his work maintaining and caring for the family garden and business at Bartram’s with his younger brother John, Jr.

Portrait of William Hamilton and his niece Ann Hamilton Lyle. (Image: Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Just up the river, William Hamilton (grandson of prominent Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton, whose defense of John Peter Zenger established freedom of the press) established his estate, The Woodlands, in the style of an English country house. Hamilton inherited the estate from his father in 1747 when he was just two years old and had, over the course of his adult life, parceled together roughly 500 acres along the western bank, including much of what is now the campuses of Penn and Drexel. Hamilton was an Anglophile and an enthusiastic amateur botanist and plant collector. An extended visit to England in the mid-1780s inspired the neoclassical remodel of his Philadelphia estate, recognized as the earliest example of Federal architecture in the country, and heavily influenced his approach to landscape design. Thomas Jefferson, who was a frequent visitor to both Bartram’s Garden and The Woodlands, once remarked that Hamilton’s estate was “the only rival which I have known in America to what may be seen in England.” Hamilton was particularly interested in collecting rare and exotic plants, introducing a number of exotic species to the U.S. through his massive greenhouse complex which is believed to have housed upwards of 9,000 species.

The Woodlands and Bartram’s Garden formed the nexus of the country’s early botany scene and helped spur a regional horticultural economy that persisted for generations. Prominent naturalists, politicians, and members of the gentry would often stop at one or both gardens when travelling into the city. The two Williams frequently connected over their shared interest in plants and botany, often exchanging letters, plants, seeds and services. This relationship is best illustrated in their correspondence, which was frequent and familiar and often involved arranging the viewing, sharing, and trading of plant material.

A photograph of the Gingko at Bartram’s Garden from 1924 captioned “Oldest Gingko in America.” After William Hamilton imported the first Gingko biloba into the country, he kept two on his property at The Woodlands and sent the third as a gift to William Bartram. The two at The Woodlands no longer stand, but the impressive Gingko at Bartram’s still does and is recognized as the oldest living example in North America. (Photo: John Bowman Bartram Special Collections Library)

In a letter[1] to William Bartram on November 7, 1796 Hamilton wrote:

Dear Sir

I must beg the favor of you to make a sketch of the Senecio nova, floribunda as it now blooms in my Hot House. For this obligation I will make you any compensation in my power. After this day it cannot be done this Season as its beauty is already on the decline.

I have moreover in my Hands at this moment, just arrived from England near 100 coloured plates mostly of new plants (some of them from Botany Bay) which you ought not to lose the opportunity of viewing & they are immediately to be return’d to the gentleman who left them here. I hope therefore you will oblige yourself as well as me by coming here as soon as you can after receiving this & that you will come prepared to make the sketch I have required, in which I am more interested for the Honor of American gardening than you are aware of. I have seen a figure & description of this plant as it flower’d last season for the first time in Europe, under the name of Senecio Chrysanthemum by which I find it flower’d with me before it was known in Europe.

I am dear Sir truly

Your friend & humble Servt.

W Hamilton

Both Williams also had connections to the University of Pennsylvania, then known as the College of Philadelphia, particularly to Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, chair of Materia Medica and the sole professor of botany at the university. Bartram’s Garden and The Woodlands functioned as outdoor laboratories to supplement lectures and William Bartram often leant his services as a botanical illustrator to assist Barton. The relationship between the three ensured the university’s position as the best place in the country for the study of botany and both Hamilton and Bartram assisted in procuring and sharing noteworthy and interesting plant specimens. In the following letter, William Bartram writes Dr. Barton about the first blue hydrangea imported to America, on display at William Hamilton’s garden at the Woodlands:

P.S. Come see us as soon as convenient. Have you seen the most beautiful Hydrangia [sic] from china now in flower at Hamiltion’s Gardens at the Woodlands? if not it is well worth a visit. The Cœlestial blue of the flowers is inexpressebly [sic] pleasing. [2]

An Illustration from Frank H. Taylor ca. 1922 showing the Woodlands mansion and John Bartram’s house as examples of country mansions from “a time when the unpolluted tide-water Schuylkill River was bordered by fine country seats.” (Image: Library Company of Philadelphia)

Hamilton frequently entertained guests at The Woodlands and his dinners and his gatherings, more often than not, involved lengthy discussions about plants and botany supplemented by demonstrations of species from his greenhouse. These were sometimes even coordinated around significant bloom times of his most impressive rare species, which would be brought in to the house to be observed and appreciated throughout the meal. In the following letter,[3] Hamilton requests a sample of a particular variety of grape from Bartram to serve the dual purpose of botany and dessert at an upcoming dinner:

My dear Sir

Mr Pursh tells me that he was at your house yesterday & that you shewed him a white grape which you called Blands grape—From what I have heard you say, I have always supposed it a dark fruit & my curiosity is exited to understand the Business. I will therefore thank you to send me a specimen of the fruit by the bearer. If it is ripe & you can spare them, you will oblige me by sending as many as will fill a plate as if the fruit good, it would serve as an interesting part of our Desert [sic] at dinner to day for Mr. & Mrs. Merry whom I expect will be here—

—I am most sincerely

Your friend

W. H.

Stay tuned as we highlight more of the fascinating botanical connections between these two sites!

Upcoming Posts:

Found in the Floorboards: 200 Year Old Seed Packets

William Bartram's Travels and the Early Naturalist's Library

Think Local Swap Global: 18th Century Approaches to Plant Collecting

From Seed Shack to Plant Palace: Evolutions in Greenhouse Technologies

The 19th Century Commercial Nursery

By Starr Herr-Cardillo

[1] William Hamilton to William Bartram, November 7, 1796, Gray Herbarium Autographs 3:17a, Harvard University.

[2] William Bartram to Benjamin Smith Barton, July 16, 1800, Barton Delafield Collection, American Philosophical Society.

[3] William Hamilton to William Bartram, circa 1803-1805, Bartram Papers 4:49b, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

This blog series is made possible by Penn Sustainability and PennDesign.

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden and the Invention of the National Park

Yellowstone National Park is a geologist’s paradise: the nearly three and a half thousand square miles of land include the largest volcanic system in North America, extensive geothermal activity caused by a subterranean magma chamber and the highest concentration of geysers in the world. Yet the park is also appreciated by millions of visitors each year for its sheer beauty and pristine landscape. The double appeal of Yellowstone goes all the way back to its early history when a team of scientists and artists were dispatched to explore the yet-uncharted region. The combination of their academic and creative accomplishments was instrumental in the establishment of Yellowstone as the first national park of the United States.

A photograph of the Summit of Jupiter Terraces taken by William H. Jackson. Paintings and photographs of Yellowstone were crucial to its establishment as a national park.

Ferdinand Hayden, the leader of an 1871 surveying expedition to the Yellowstone area.

In the years following the Civil War, the region that is today Yellowstone was a mystery to most Americans. Could accounts of hot water spouting from the ground or rumblings underfoot possibly be credible? And more importantly, was the land suitable for agricultural development? In 1871, the General Land Office turned to Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, an expert geologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania (who is now buried at The Woodlands Cemetery) to answer these questions. Hayden put together a team of over thirty men, wisely including Civil War photographer William H. Jackson and esteemed painter Thomas Moran, and set off on what would be the largest of four “Great Surveys” of the American West.

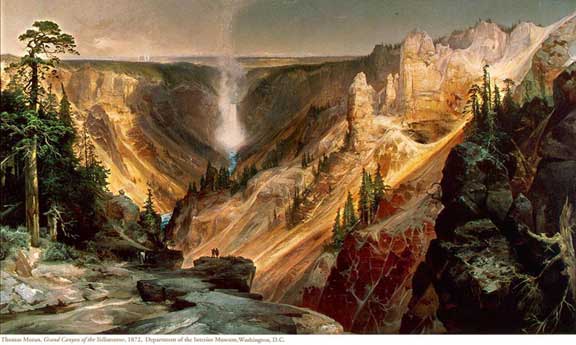

After a long cross-country voyage, the explorers arrived in Yellowstone and were amazed with what they found. While the paleontologists, geophysicists and lithologists in the group set about collecting geological data and rock samples, Jackson and Moran visually recorded the natural landscape. By Moran’s account, he “took great pains with delineation of the form and texture of the rocks” which he “realized to the farthest point I could carry them”. This creative approach is exhibited in The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone which Moran completed in 1872. The dramatic oil painting highlights the formations and stratifications of the rock with great accuracy while capturing, as Moran hoped to, “the character of that region.”

In Moran's The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone sunlight falls on the park's spectacular rock formations, which are depicted with geological accuracy.

When Ferdinand Hayden returned to the East from his expedition, he had a vision for Yellowstone that was unprecedented amid the pioneer mentality of the 19th century United States. Hayden wanted Yellowstone to remain undeveloped, as a natural space available to generations of future Americans. Along with the proposal he submitted to Congress, Hayden included Jackson’s photographs and some of Moran’s watercolors. These beautiful visual depictions of the region were crucial in persuading congressmen (most of whom had not seen for themselves the magnificence of the West) to establish Yellowstone as “a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” in 1872.

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden is buried at The Woodlands Cemetery in Section H, Lot 301.

Thanks to the enthusiasm and determination that Hayden brought to his lobbying for Yellowstone National Park, this model became broadly accepted both in the United States and around the world. Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, thirty-five natural places within the U.S. were granted this status before the National Park Service was formally signed into being in 1916. In honor of the bureau’s 100th birthday, this year’s Philadelphia Flower Show will celebrate the beauty of our national parks. Although Philadelphia and Yellowstone may not appear to have much in common, the early history of the park was determined by a resident of this city. If you’re visiting for the Flower Show this week, consider stopping by Penn’s Hayden Hall or The Woodlands to pay a visit to the final resting place of Ferdinand Vendeveer Hayden, the scientist behind America’s national parks.

By Rive Cadwallader

You can find more information about Hayden's expedition and the art it inspired from:

Jackson, W. Turrentine. "The Creation of Yellowstone National Park," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 29, No. 2 (1942): 187-206

Wagner, Virginia L. "Geological Time in Nineteenth-Century Landscape Paintings," Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 24, No. 2/3 (1989): 153-163

Paul Philippe Cret

Paul Philippe Cret, the prolific Beaux-Arts architect who designed many structures in and around Philadelphia, was born in Lyon, France in 1876. After studying in his hometown and then in Paris, Cret sailed for America to teach architecture at the University of Pennsylvania in 1903. Although he had established a his own firm in Philadelphia by 1907, Cret served in the French army for the entire span of World War I, and received several military honors. Before returning to Philadelphia in 1919, Cret designed a European memorial at the request of Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, whose son Quentin had died in combat.

Cret’s architectural firm flourished through the 1920s. After World War I, there was a high demand for monuments to commemorate people who had served. The Frankfort War Memorial at Wakeling and Large Streets was designed by Cret, as was the National Memorial Arch at Valley Forge, and several commemorative structures in France.

Beginning in 1922, Cret designed the Delaware River Bridge (now the Benjamin Franklin Bridge), which at the time of its completion was the longest suspension bridge in the world.

The construction of the bridge was extremely technical and complicated, and required workers to dig to the bedrock at the bottom of the river in chambers so highly pressurized that the laborers could not expel enough air to whistle while they tunneled. The building of the bridge cost $37,103,765.42 (over eight million dollars more than expected) but was employed by 32,000 vehicles over the course of the first day it was opened. Cret subsequently drafted the University Avenue Bridge and the Henry Avenue Bridge. In 2012, Courier Post went behind the scenes of the Ben Franklin Bridge and shared this video.

Cret began making plans for the Barnes Foundation in Merion, PA in 1923 and competed the project two years later. Not long after, he collaborated with Jacques Greber to design the Rodin Museum, and in 1936, Cret drafted the plan for the gates to The Woodlands Cemetery.

Throughout his career, Cret advised several major universities including Brown, Harvard, Penn and the University of Texas at Austin on campus architecture.

On September 8, 1945 (68 years ago, yesterday) Paul Cret died of heart disease in Philadelphia, at age 69. He is buried in Section K of The Woodlands, beneath a marker of his own design. Many of his creations still stand today in Philadelphia, and have made an immense impression on the architectural fabric of the city.

by Rive Cadwallader