Welcome to the first edition of our "Birding at The Woodlands" blog series! Resident birding expert, "Toribird" will be reporting on recent birding news happening at The Woodlands over the next few months. Stay tuned for updates all things zines, birds, and of course, TORIBIRD!

I (Victoria, "Toribird") have spent the last couple months working on a zine-guide to birds of The Woodlands. I got my start here when Jessica Baumert and I teamed up to catch an escaped parakeet. During the hours-long process, Jessica realized that I love birds and birding, and I was offered an internship at The Woodlands.

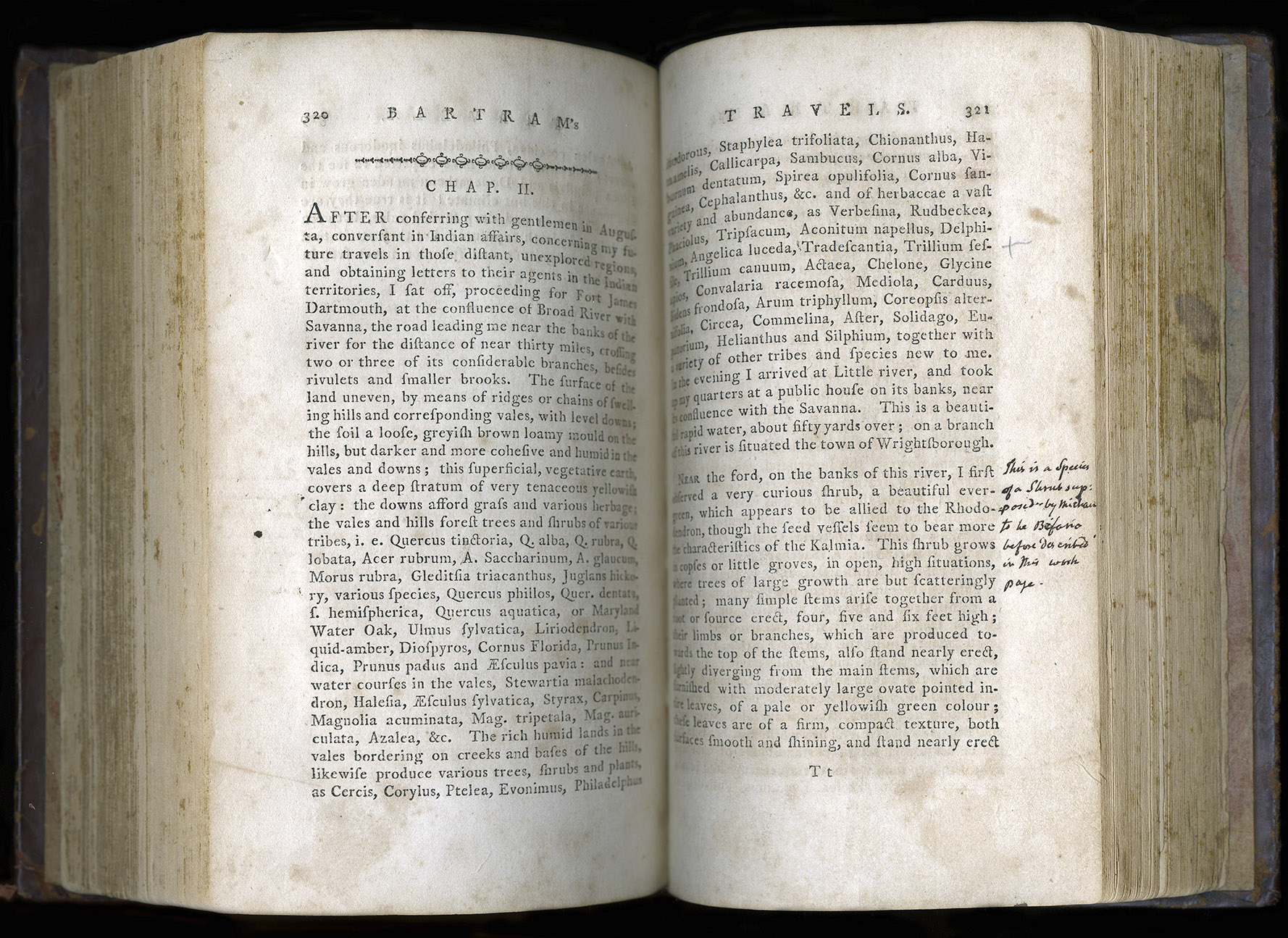

Toribird (left) with zine illustrator Jess Ruggiero (right) at the Zine Release Party.

The zine was one of a few birding projects that I have worked on here. We began with birding tips shared on our blog. Then, I led two bird walks and taught how to make pinecone-bird feeders on Halloween Family Fun Day. I also led a lantern-lit walk on the Winter Solstice.

Just recently, on the evening of May 22nd, my zine had its launch party. The illustrator, Jess Ruggiero attended, and I really enjoyed getting to meet her! As part of the festivities, I led two bird walks. Jess went along for one, and she seemed very exited to see the birds that she had spent so much time drawing; I liked sharing them with her.

Despite rain threatening, a nice group showed up. They were an interested, supportive, group and a pleasure to lead on the walks! All in all, I had lots of fun chatting and sharing what I knew, and I think all our visitors had fun too!

If you're interested in purchasing a copy of the Guide to Birding at The Woodlands Zine, you can pick one up for $5 at an upcoming Woodlands Event. You can also donate $5 to The Woodlands and have a copy mailed to you. Donations can be made here.

Walks and parties aside, let's have a look at what's going on bird-wise at the Woodlands right now:

Spring migration is pretty much over. However, this means that each and every one of our summer residents are here. Some examples of birds that have returned are Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Northern Rough-winged Swallow, Grey Catbird, Yellow Warbler, and Chipping Sparrow. These birds are all common at The Woodlands during the warmer months of the year. See if you can spot them!

Additionally, many songbirds are building nests and laying eggs right now. If you see a bird carrying rope, mud, grass, or other materials, you can know that it is busy constructing a cozy nest. Follow it and try to find their nest! Also, several birds are singing to attract a mate and defend their territory, though not as many as earlier in the year. Soon, you will be able to see this year's hatchlings.

Here is a list of birds that are easy to see at the Woodlands right now:

American Robin resting its wings on a headstone at The Woodlands. Photo by Toribird.

Ring-billed Gull - look for them near the river

Mourning Dove

Chimney Swift

Northern Flicker - A woodpecker, though that is not in its name

Eastern Kingbird - They seem to like sitting on top of headstones and catching bugs from there

Northern Rough-winged Swallow

American Robin

Grey Catbird - A well-named bird, as it is grey with a call that sounds like a nasal 'meow'

European Starling - An invasive bird introduced from Europe

Chipping Sparrow

Baltimore Oriole

Brown-headed Cowbird - A brood parasite, laying its eggs in other birds' nests

Looking for even more birding fun? Find out which type of bird YOU are based on your personality with my quiz. You can take the quiz here.

Written by: Victoria Sindlinger