As Pride Month comes to an end, we are highlighting stories that celebrate LGBTQ+ love and partnership. While we have no shortage of influential figures to commemorate here at The Woodlands, we want to take this opportunity to re-introduce some of our favorite notables whose relationships defied social constructs of their time.

How do we know they were a part of the LGBTQ+ community? In truth, we cannot assume how the following couples would have self-identified today. It was not until a cultural shift in the late 19th century that “lesbian,” “gay,” and “bisexual” were used to describe a person’s sexual identity, and not popularized until later in the 20th century [1]. However, it is certain that these relationships shared a deep bond and drew happiness and inspiration from their partners. We are excited to share the stories we have uncovered and in doing so hope to paint a fuller picture of these remarkable people.

Mary Grew and Margaret Burleigh: Women for Women

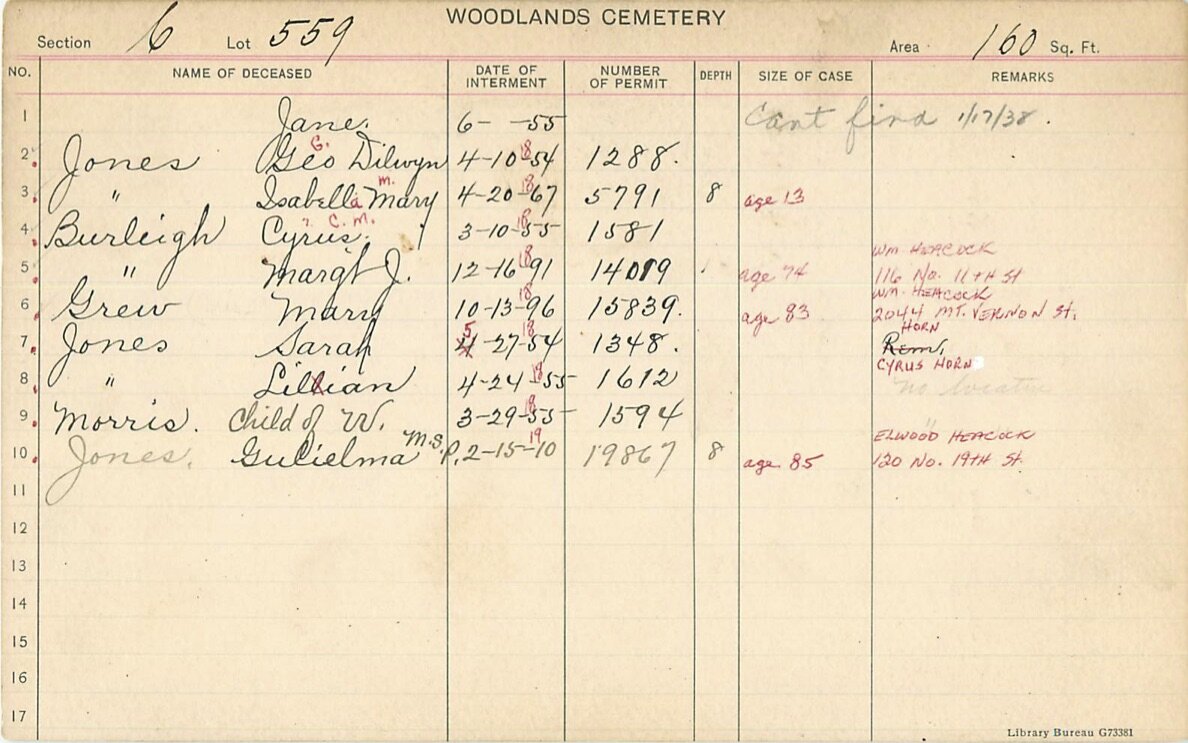

As a renowned activist, it is perhaps unsurprising that Mary Grew’s lifelong partner, Margaret Burleigh (1817-1891), was also a fierce supporter of the same causes. Originally a schoolteacher from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Margaret met Mary through their work in both the anti-slavery and women's rights movements. In 1855, Margaret married a mutual friend and colleague, Cyrus M. Burleigh. However, when Cyrus passed away one month later from tuberculosis, Margaret lived the rest of her life with Mary Grew [2]. Together, the pair continued to push back against criticism of women from within and outside of the anti-slavery movement by speaking at public conferences and creating spaces for women in activism.

Mary and Margaret unapologetically lived outside of the traditional marriage model as "romantic friends": a devotion and affection described by contemporaries as surpassing the love of men. Many similar correspondences between Mary and friends provide insight into Mary and Margaret's emotional bond, a "union with another soul" for nearly fifty years, as Mary describes it [3]. However, few are more illuminating and eloquent as Mary’s response to a condolence letter from a younger suffragist, Isabel Howland, after Margaret’s death in 1893:

"Your words respecting my beloved friend touch me deeply. Evidently you understood her fine character; & you comprehended and appreciated, as few persons do, the nature of the relation which existed, which existed [still, despite the death of Burleigh's body] between her and myself… To me it seems to have been a closer union than that of most marriages. We know that there have been other such between two men, & also between two women. And why should there not be. Love is spiritual, love passion is sexual" [4].

Margaret Burleigh can be visited at the Woodlands in Section C Lot 559, her grave resting between Cyrus Burleigh and Mary Grew.

To learn more about Mary Grew’s life and activism, you can find our digital tour here.

To read more about Mary and Margaret’s relationship, you can also explore the twitter thread by the Daily Suffragist here.

Jessie Wilcox Smith and the Red Rose Girls: Boston Marriage & Blossoming Love

After completing art classes together at Drexel Institute for Arts and Sciences in 1897, Jessie Willcox Smith, Violet Oakley, and Elizabeth Shippen Green decided to share an apartment at 1523 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, kicking off a fourteen-year communal living arrangement. It was not unusual for women art students to share an apartment, which was often called “baching it” or “a Boston marriage,” but the trio certainly developed an exceptional friendship centered around their artwork. Each financially and socially independent, their choice to live and support one another went beyond the traditional social conventions and speaks to their profound relationships. When Henrietta Cozens joined the trio during their time at the Red Rose Inn as a partner and general housekeeper, the group made a solemn agreement to stay together for life and took a common surname “Cogs” after the first letter of their last names.

When their living arrangements diverged in 1911, the friends each entered lifelong partnerships: Jessie Wilcox Smith and Henrietta Cozens, Elizabeth and Huger Elliott, and Violet Oakley and Edith Emerson. In 1920 when Huger Elliott wrote to Jessie and Henrietta on behalf of Elizabeth, he relayed his wife’s humorous message, “Yitty One… Sends her YUV & YUV to Jed-Jed and Hen-Hen: I’ve told her that if she bursts forth into baby-talk while we are with you this summer I’ll get a divorce and marry Mrs. Blackenburg!” [5]. While many contemporaries and scholars have contemplated the nature of the relationships of the Red Rose Girls, it is clear they shared a deep fondness and love for each other which never diminished.

You can visit the grave of Jessie Wilcox Smith here at the Woodlands in Section F, Lot #220.

To delve more into the careers of Jessie Wilcox Smith and the Red Rose girls as illustrators during the turn of the century, check out the blog post “Jessie Wilcox Smith & The Red Rose Girls” here.

Anne Hampton Brewster and Charlotte Cushman: A Star-Crossed Romance

Another permanent resident at the Woodlands is Anne Hampton Brewster (1818-1892), one of the first American female foreign correspondents. Although Anne never had a lifelong partner, her romantic life is often characterized by an early affair with Charlotte Cushman (1816–76).

Painting of Charlotte Cushman by Thomas Sully donated by Anne Hampton to the Library Company of Philadelphia.

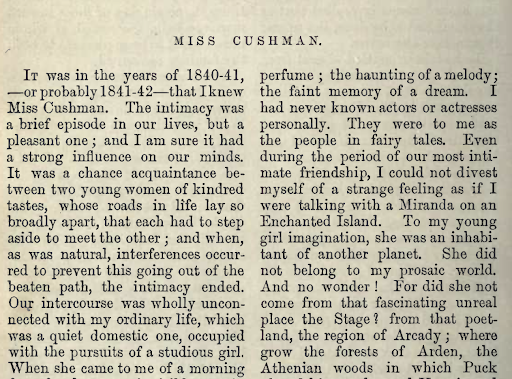

Charlotte was a prominent American actress who reached international fame for several roles including Romeo, Lady Macbeth, and Nancy from Oliver’s Twist. When Charlotte and Anne met, Charlotte was acting in Philadelphia as well as managing the Walnut Street Theatre. Recounting the affair in her diary in 1849, Anne describes their intimate relationship as a “glorious beam of sunshine in my existence” [6]. Their time together was often spent reading literature and rehearsing performances, a pursuit which seemed to delight both with inspiration and passion for their work. Notes sketched in pencil from Charlottes prompter’s stand passed between the two women, arranging meetings and sharing lines of prose [7]. The affair was cut short by Anne’s brother, who allegedly disapproved of their relationship. Charlotte was known to openly engage in romantic same-sex relationships, which perhaps caused the brother’s scrutiny. Soon after, Charlotte would leave to pursue her career in England. Anne was greatly affected by their separation and wrote in her diary she felt, “out at sea without rudder or compass.”[8]

Article from Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine by Anne Hampton Brewster about her affair with Charlotte.

Despite separation, their letters reveal they continued to support each other--Charlotte even encouraged Anne’s foreign travels. In their later years, both women lived in a vibrant expat community in Rome. Though they remained socially in the same circles, Anne says their relationship was never as intimate again [9]. In remembrance of their brief affair, Anne later donated a portrait of Charlotte that was painted by Thomas Sully to the Library Company of Philadelphia.

You can visit Anne Hampton Brewster’s final resting place at the Woodlands in Section D, Lot #120.

Glimpse into the life of journalist of Anne Hampton Brewster, by reading our digital tour here.

Through exploring the personal lives of some of our permanent residents, we are inspired by not only their personal accomplishments but also by their relationships which pushed past societal expectations. We are committed to continue researching LGBTQ+ history at The Woodlands, and look forward to sharing more stories in the future.

Written by:

Blair Horton

Sources:

King, Cornelia S., and Don James McLaughlin. “Schoolgirl Smashes, David-and-Jonathan Relationships, and Champagne Friendships: Mining the Archive for LGBT History.” Pennsylvania Legacies, vol. 16, no. 1, 2016, pp. 12–19., doi:10.5215/pennlega.16.1.0012.

Brown, Ira V. Mary Grew: Abolitionist and Feminist: 1813-1896. Susquehanna Univ. Press U.a., 1991.

Mott Manuscripts, SFHL-MSS-035, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College. Item A00182571.

Faderman, Lillian. To Believe In Women : What Lesbians Have Done for America--a History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999: 20-21.

Carter, Alice A. The Red Rose girls: an uncommon story of art and love. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2000.

“Being Single.” Edited by Library Company of Philadelphia, That's So Gay: Outing Early America, www.librarycompany.org/gayatlcp/section8.html.

Brewster, Anne Hampton. “Miss Cushman”, Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Aug 1878,” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed June 23, 2021, https://archive.org/details/blackwoodsmagaz124edinuoft/page/10/mode/2up.

“Being Single.” Edited by Library Company of Philadelphia, That's So Gay: Outing Early America, www.librarycompany.org/gayatlcp/section8.html.

Brewster, Anne Hampton. “Miss Cushman”, Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Aug 1878,” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed June 23, 2021, https://archive.org/details/blackwoodsmagaz124edinuoft/page/10/mode/2up.