If you’re a regular visitor of The Woodlands or follow us on social media, you have probably noticed that a number of “cradle graves” (the headstones with bathtub-shaped planters extending out in front) have finally been getting some attention and are filling up, once again, with flowers. This wonderful development is the result of our newest volunteer program The Woodlands Grave Gardeners.

Beginning in February, a large group of volunteer gardeners attended a series of workshops culminating in the planting of over seventy Victorian-inspired gardens in cradle graves around The Woodlands. The preliminary workshops and lectures prepared the gardeners for the actual hands-on planting of their graves, provided information on appropriate heirloom plant varieties, and provided historical context for the program.

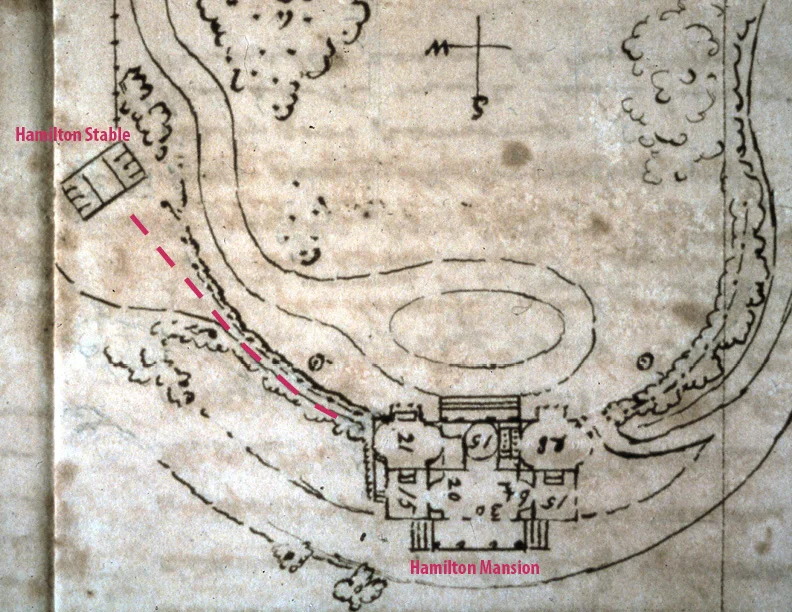

A representative from the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society gives a planting demonstration. Photo: Ryan Collerd

Gardening in cradle graves is essentially container gardening or trough gardening. Our planting list, crafted and curated by heirloom plant expert Nicole Juday, includes varietals that would have been common in this area in Victorian times and is full of perennials, roses, bulbs and ferns. The list is a guideline, though using period-appropriate, heirloom flowers and plants is fundamental to the program. Luckily, these tend to be more fragrant than contemporary varieties and also naturalize readily (meaning they will spread out and re-seed). In fact, some of the cradle graves already contained bulbs that had done just this (turns out historic cemeteries are great spots for finding heirloom flowers!). Nicole helped us split existing bulb clusters into smaller bunches that we shared with the gardeners so we could spread the love! So, what’s the biggest no-no when planting an “authentic” Victorian garden? No variegated leaves. Really—they weren’t around back then!

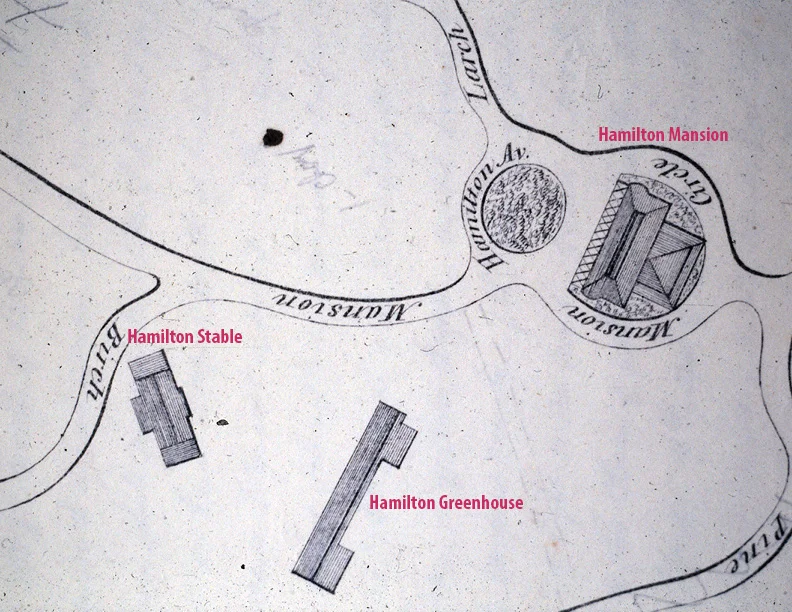

Gardeners supplemented seeds and plugs with plants purchased from the Bartram's Garden spring plant sale. Photo: Ryan Collerd

The cradle grave typology was particularly popular from the late 19th through early 20th century. At one point, most would have been planted and maintained, but over the course of the past century or so, they have come to sit empty. It may seem a little odd to get that up close and personal with someone’s final resting place, especially when taking a shovel to the dirt. Interestingly, most of our gardeners have reported that they really enjoy this aspect of the program; taking time to care for someone’s lot lets them reflect and brings a sense of calm. Some have even gone lengths to do genealogical research on their lot residents, uncovering interesting details that inspire whimsical and imaginative planting themes.

As one of the first rural cemeteries in the city, The Woodlands also functioned as one of the earliest public parks. In the Victorian Era, it was common for family members to maintain gardens in their family cemetery plots and even to spend time on the weekends picnicking and enjoying the space. In fact, The Woodlands became so crowded by those seeking a pleasant weekend respite that in 1852, management had to implement an admissions system requiring tickets for entry during peak hours. Lot owners were granted tickets automatically, but the rest were distributed to the public per managerial discretion.[1] Part of what continues to make The Woodlands such a beloved site is that it welcomes the public every day from dawn till dusk for a broad range of activities and uses. The Grave Gardeners program takes things a step farther and allows users to be active participants in beautifying and caring for the space once again.

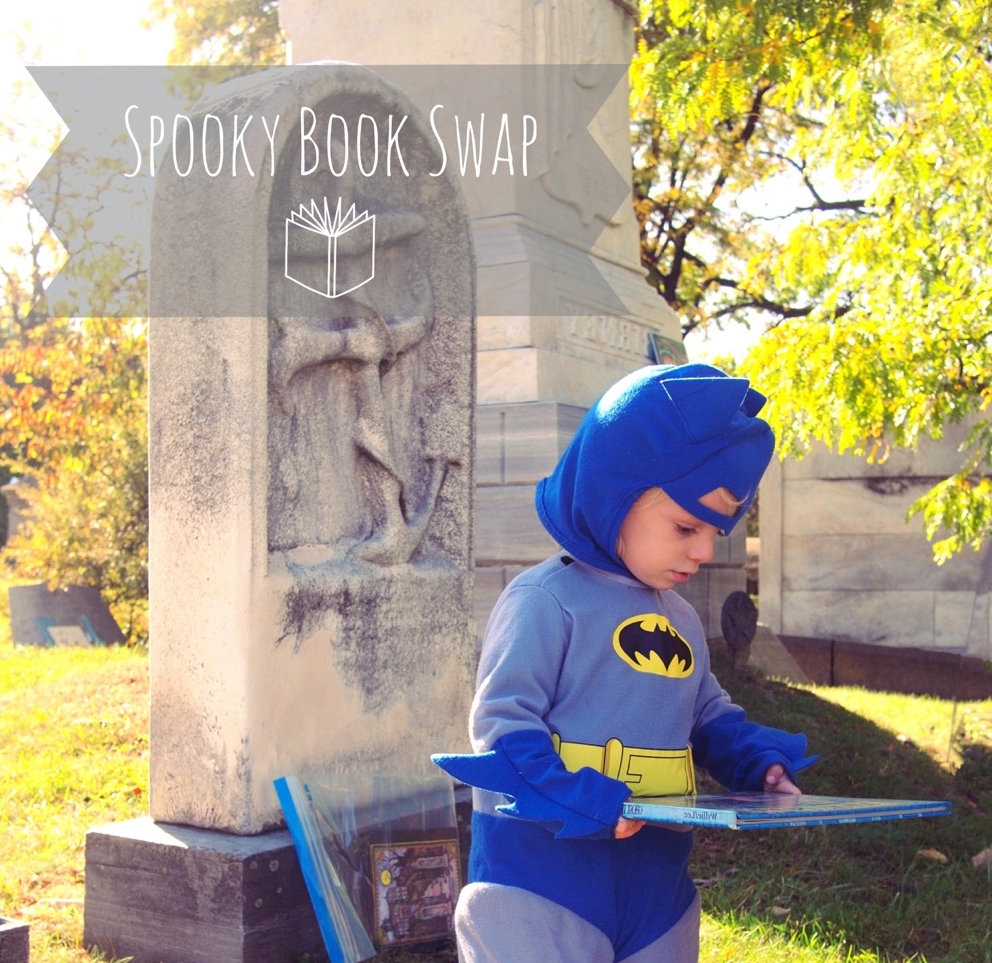

Ferns and flowers give the gardens a Victorian feel. Photos: Ryan Collerd

It has been wonderful to watch our first season of planting unfold. For the pilot run of the program we limited planting to sections that are close to the Mansion and to Center Circle, but moving forward we hope to complete an inventory of all cradle graves on site (we estimate there are between 300-400). We plan to expand the program next year and will be accepting new applications in the fall. In anticipation, we have put together an outstanding bulb order for fall planting, focused on heirloom varieties from the 18th to 19th century. The order was tailored to cradle grave gardening, but also includes bulbs that we will plant en masse throughout the cemetery. Meaning, we anticipate thousands of fragrant spring blooms!

Come enjoy the gardens in person and join us Saturday, September 17th when we will host our inaugural Grave Garden Fete, a day full of cemetery picnicking, plant and flower-related workshops, demonstrations and garden-viewing. It will be a throwback to the Victorian days meant to showcase our Grave Gardens, so bring family, food and drink and lay out a blanket to enjoy the beauty of The Woodlands! More details on the Grave Garden Fete HERE.

By Starr Herr-Cardillo

Photos: Ryan Collerd

[1] Wunsch, Aaron. “Woodlands Cemetery,” HALS No. PA-5