Yellowstone National Park is a geologist’s paradise: the nearly three and a half thousand square miles of land include the largest volcanic system in North America, extensive geothermal activity caused by a subterranean magma chamber and the highest concentration of geysers in the world. Yet the park is also appreciated by millions of visitors each year for its sheer beauty and pristine landscape. The double appeal of Yellowstone goes all the way back to its early history when a team of scientists and artists were dispatched to explore the yet-uncharted region. The combination of their academic and creative accomplishments was instrumental in the establishment of Yellowstone as the first national park of the United States.

A photograph of the Summit of Jupiter Terraces taken by William H. Jackson. Paintings and photographs of Yellowstone were crucial to its establishment as a national park.

Ferdinand Hayden, the leader of an 1871 surveying expedition to the Yellowstone area.

In the years following the Civil War, the region that is today Yellowstone was a mystery to most Americans. Could accounts of hot water spouting from the ground or rumblings underfoot possibly be credible? And more importantly, was the land suitable for agricultural development? In 1871, the General Land Office turned to Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, an expert geologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania (who is now buried at The Woodlands Cemetery) to answer these questions. Hayden put together a team of over thirty men, wisely including Civil War photographer William H. Jackson and esteemed painter Thomas Moran, and set off on what would be the largest of four “Great Surveys” of the American West.

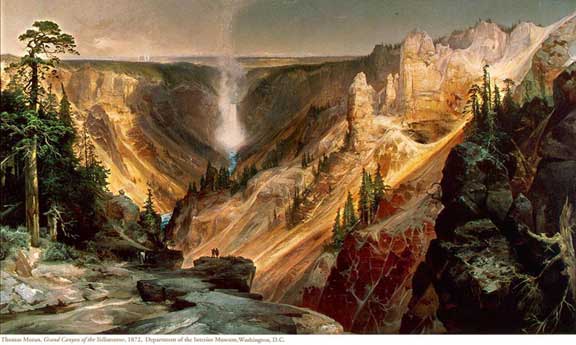

After a long cross-country voyage, the explorers arrived in Yellowstone and were amazed with what they found. While the paleontologists, geophysicists and lithologists in the group set about collecting geological data and rock samples, Jackson and Moran visually recorded the natural landscape. By Moran’s account, he “took great pains with delineation of the form and texture of the rocks” which he “realized to the farthest point I could carry them”. This creative approach is exhibited in The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone which Moran completed in 1872. The dramatic oil painting highlights the formations and stratifications of the rock with great accuracy while capturing, as Moran hoped to, “the character of that region.”

In Moran's The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone sunlight falls on the park's spectacular rock formations, which are depicted with geological accuracy.

When Ferdinand Hayden returned to the East from his expedition, he had a vision for Yellowstone that was unprecedented amid the pioneer mentality of the 19th century United States. Hayden wanted Yellowstone to remain undeveloped, as a natural space available to generations of future Americans. Along with the proposal he submitted to Congress, Hayden included Jackson’s photographs and some of Moran’s watercolors. These beautiful visual depictions of the region were crucial in persuading congressmen (most of whom had not seen for themselves the magnificence of the West) to establish Yellowstone as “a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” in 1872.

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden is buried at The Woodlands Cemetery in Section H, Lot 301.

Thanks to the enthusiasm and determination that Hayden brought to his lobbying for Yellowstone National Park, this model became broadly accepted both in the United States and around the world. Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, thirty-five natural places within the U.S. were granted this status before the National Park Service was formally signed into being in 1916. In honor of the bureau’s 100th birthday, this year’s Philadelphia Flower Show will celebrate the beauty of our national parks. Although Philadelphia and Yellowstone may not appear to have much in common, the early history of the park was determined by a resident of this city. If you’re visiting for the Flower Show this week, consider stopping by Penn’s Hayden Hall or The Woodlands to pay a visit to the final resting place of Ferdinand Vendeveer Hayden, the scientist behind America’s national parks.

By Rive Cadwallader

You can find more information about Hayden's expedition and the art it inspired from:

Jackson, W. Turrentine. "The Creation of Yellowstone National Park," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 29, No. 2 (1942): 187-206

Wagner, Virginia L. "Geological Time in Nineteenth-Century Landscape Paintings," Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 24, No. 2/3 (1989): 153-163